The blog post where I intend to introduce my People Power Pale Ale seems like a pretty good time to also begin a series I’d like to do on each of the four primary ingredients in beer, which was mentioned on our first blog post. All beer (with the exception of certain antiquated styles) is comprised of these four ingredients, but the permutations that can be produced by modifying their usage are endless. And the ingredient that can be perhaps manipulated in the most ways to produce the most unique, intense, and flavorful beers is the simple, unassuming hop.

Hops are the female flower of a single species of rhizome-producing plant in the same family as cannabis. They were first cultivated nearly 1,300 years ago, originally for medicinal purposes, though their first documented usage in beer wasn’t until the 11th century. Many people owe a debt of gratitude to whomever that accidental genius was, as hops are now used as the predominant bittering agent in nearly every style of beer and the primarily flavoring agent in many styles.

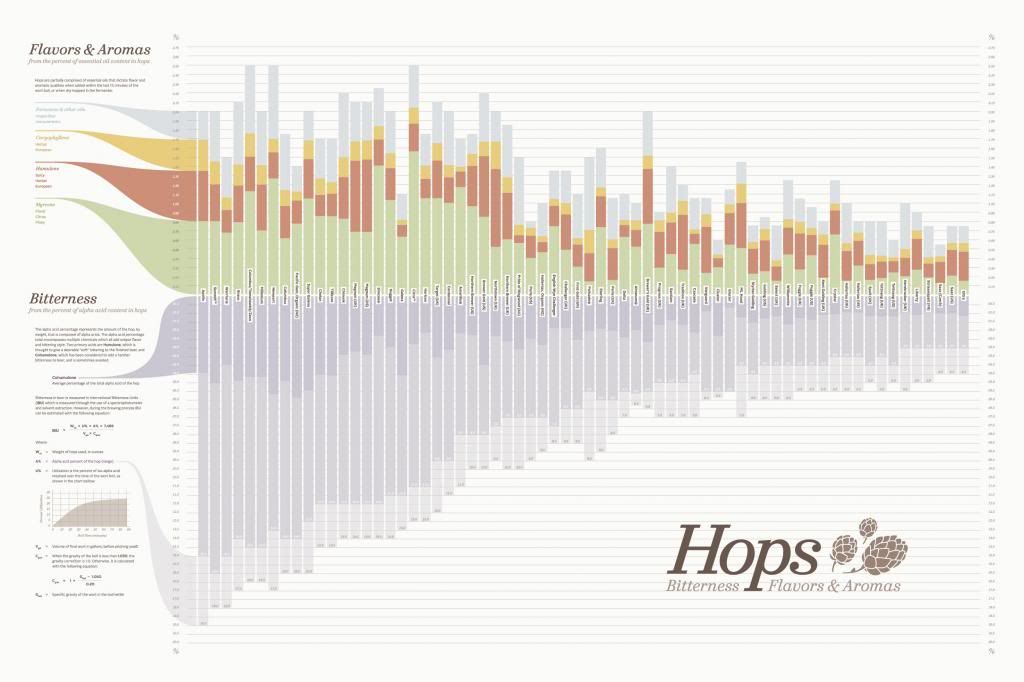

Those of us in the beer-o-sphere (if this wasn’t a thing before, it is now) who worship at the altar of the hop call ourselves “hop heads,” and I’m a proud member of this club. I’m not sure what makes hop-forward beers so appealing, but their position in the craft beer movement and the public imagination has never been higher than it is right now. Maybe it’s the complexity of the flavors, or maybe it’s their familiarity to so many intensely flavored and aromatic compounds— grapefruit, pinecones, tobacco, lemongrass, leather, mango, stone fruit, chives, mint. Each hop variety, and there are dozens upon dozens of varieties, with more experimental hybrids being released each fall, contains a dizzying assortment of acids and oils that contribute notes reminiscent of the above and more in various proportions.

Historically, hops were divided in to two (sometimes overlapping) categories, depending upon their primary usage. “Bittering” hops were those that were higher in what we refer to as “alpha acids,” which, when boiled for long periods of time, become soluble and are extracted from the hop cones— providing the bitterness needed to balance the residual sugars that remain in a beer after fermentation. On the other hand, “aroma” or “finishing” hops were those that were generally lower in alpha acids, but higher in flavorful and aromatic essential oils; these oils boil out of the finished beer very quickly, so finishing hops were typically added very close to or at the end of the boiling of the beer to preserve as many of them as possible.

The craft beer movement has tried to move beyond these descriptions, and advances in brewing technology (as well as scientific analysis) have given us a clearer picture of what makes hops contribute to beer in the ways that they do. No longer are hops merely added to the boiling wort (note: wort is what we call the beer before it’s beer) at one or two specified intervals. New techniques (and sometimes very old, rediscovered techniques) like first wort and mash hopping involve adding the hops to the wort before it is brought to a boil, allowing the volatile oils and acids to bind to grain proteins and stabilize at lower temperatures to survive the boil in ways that present new and exciting flavors; big additions of flavorful hops at the end of a boil while the beer is cooling allow oils that would boil away at the boiling point of water but can survive at lower temperatures to be extracted more fully in to the beer while also imparting far less bitterness; and “dry hopping,” the act of hopping a beer at ambient or fermentation temperatures (or sometimes, directly in the bottle or keg!) allow an entirely different combination of flavor and aroma compounds to be extracted and merged with the finished beer.

Add these techniques to the new hop strains that are being hybridized and bred every year— one of the recent experimental hops that just made its debut is being described by brewers as producing an aroma reminiscent of “chocolate coconut,” while others are showcasing melon, blueberry, and apricot. The end result are beers that go far beyond the antiquated “bitter” vs. “not bitter” divide. Sure, many “hop forward” beers are still bracingly bittered with hops that impart a rough, catty bitterness; however, more and more are relatively mildly bittered, or are bittered with hops that produce a smooth, pleasant bitterness, and focus primarily on showcasing the herbal, woody, citrusy essential oils that make hops so enticing.

Our People Power Pale Ale fits in to this category. Though this beer goes a little beyond the stylistic range of a traditional Pale Ale (we’ll call it an “Extra Pale Ale”), we’d like to think it does so in all the right ways. A grain bill with small additions of Munich, Caramel, and Melanoiden malts provides a backbone that’s simple, with hints of graininess, roast, and biscuit… subtle, nuanced, and well balanced. But we’re just getting started. Beginning with a healthy dose of first wort hops, this beer is boiled a full 50 minutes before additional hops even approach the kettle. This late, late addition ensures that we’re retaining as many of those delicate, volatile aromatic oils as possible… and what a late addition it is. We double the initial amount of hops added in the “aroma” portion of the addition schedule, triple it after flameout and while we whirlpool the hops at a sub-boiling temperature, and quadruple the initial addition during the dry-hopping stage. The end result is a beer that actually “breaks” most of the formulas brewers traditionally use to calculate bitterness – despite the numbers telling us this beer should be off-the-charts bitter, the final product is smooth, crisp, and bursting with tropical juicy goodness, reminiscent of apricot, mango, orange, and nectarine, with only a mild, smooth bitterness balancing the residual sweetness in the malt backbone.

This is a beer that’s riding the crest of the hop revolution wave, and as good as any you’ll fine at the finest craft brewery anywhere in the world. No more are brewers trying to make the most bitter, painful-to-consume IPAs; instead, experimentation is focusing on unlocking the true potential of the hop, that mysterious little floral cone that began its time in beer as a preservative but has become a focal point of craftsmanship and flavor potential as the craft era dawns. Our People Power Pale Ale celebrates the hop as a symbol of the power of a movement that has redefined the beverage that beer can be and mean to a culture, and—we hope—what beer can mean to you.