Purity, Pride, and the history of the Pilsner

We’re big fans of history here at The Cebruery, and we love how different styles of and traditions pertaining to beer can tell us about an area or a people. Viewing a region’s culture and values through the prism of beer is not only instructive from a retrospective point of view–learning about the past, academically–but can also inform the future. Why did one style gain traction over another style in a particular region during a particular time period? Why were certain ingredients favored over others? Was it because of the rise of a new technology? An explosion in the purchasing power of the middle class? Perhaps a period of extended and localized catastrophic drought that altered raw ingredient economics? The story of the Reinheitsgebot is one such window in to the past, and one that both strongly influences as well as flies in the face of many values held dear by craft brewers today.

The Reinheitsgebot–which is pretty much pronounced how it looks like it should be–is the oldest consumer protection law in existence. Period. Before health and food and drug administrations, before laws requiring receipts to be given to consumers and refunds to be given for defective products, before laws requiring labels to show how many calories or what ingredients a product contained … there was the Reinheitsgebot. Literally translated as “Purity Law,” the origins of the law lie with Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria. Albert came from the colorful and powerful House of Wittelsbach, a family which–in addition to ruling over the Kingdom of Bavaria for almost a millennium–provided us with two Holy Roman Emperors, one King of the Romans, two Anti-Kings of Bohemia, one King of Hungary, one King of Denmark and Norway, and one King of Greece. Point is, Albert had money and power, but–as so many men of money and power do–he also had strong opinions about beer.

And as well he should have. Germans have been brewing for at least 3,000 years, and though beer wasn’t invented in Germany, it was first commercialized there, with the first brewery on record established at Fohring near Munich around the year 800 AD. The water in and around Munich had (and still has) the perfect levels of minerals to produce bright, soft, crisp beer, and by the 13th century, the wealthy elite were cashing in and opening breweries left and right, with municipalities and towns encouraging private business owners to do the same as a source of tax revenue. By the end of the 15th century, Munich alone had thirty-eight major production breweries–not counting those small taverns and biergardens which brewed their own in small quantities in house and “off the books.”

Such was the importance of beer to the local economy that its integrity needed to be protected. There were other considerations to be had, too, of course–for instance, during particular seasons, brewers who substituted wheat and rye in to their beers when barley became too expensive caused price shocks in the grain markets, which in turn led to shortages in bread, an important and inexpensive food product for peasants and farmers. As early as 1290 A.D., local courts in Munich had ruled that substituting cheap ingredients for barley malt was forbidden, both to stabilize the aforementioned grain markets as well as to punish unscrupulous hucksters purporting to purvey a premium product (say that five times fast). The Munich City Council issued an ordinance in 1447 demanding that all brewers only use barley, hops, and water for their beers. But the law was hard to enforce without support from the royalty, and it didn’t stop watered down beer and beer made with cheap sugars and additives being brewed right outside the city limits from being brought in across local municipal lines.

So on November 30th, 1487, Albert stepped up, forcing all brewers in Munich to take a public oath of faithful allegiance to the 1447 ordinance in exchange for their continued possession of their brewing licenses. In addition, his decree instituted price controls, designed to ensure a regular, reasonably priced supply of beer for his subjects year round. The idea caught on quickly: Duke Georg in 1493 extended the 1447 ordinance and its enforcement to the duchy of Landshut in central Bavaria, and–after Albert reunified Bavaria in a series of wars late in the 15th century–his predecessor and eldest son Duke Wilhelm IV endorsed the law at a meeting in Ingolstadt of the Assembly of Estates of the Bavarian Realm as one to be followed by the entirety of the newly unified Kingdom of Bavaria on April 23rd, 1516. The penalty for violating the Reinheitsgebot? Confiscation of your beer without compensation. Pretty serious stuff.

The prohibition had profound effects on the evolution of brewing in Germany. For instance, the inclusion of hops as the only acceptable bittering and preservation agent created a booming industry in central Germany that still exists today. Prior to the Purity Law, many cheaper (and less safe) alternatives were foraged, including soot, fly agaric mushrooms, and gruit herbs such as stinging nettle.

Furthermore, the elimination of non-barley fermentables from beer standardized the brewing calendar in such a way that resulted in beer being brewed after the fall harvest of barley; that is, the beer was fermented during the cooler German winters, rather than the warmer German springs and summers. The end result was a beer that a) was fermented with the type of yeast floating around in the German air during the winter, rather than the summer, and b) that took longer to mature but ended up being cleaner and crisper than beers fermented with yeast that were active in the summer months. It’s true that no yeast was mentioned in the original text of the Purity Law, largely because it was not until the 19th century that Louis Pasteur discovered the role that microorganisms play in fermentation. Back in the 15th century, brewers generally took some of the sediment at the bottom of a batch of beer and simply transferred it to the next, a tradition that we now know resulted in the transfer of the necessary amount of yeast to ensure proper fermentation of the subsequent batch.

This seasonal shift is generally considered to be the birth of “lagering,” the process of fermenting with a bottom cropping, cold-loving yeast strain and cold conditioning beer that has given birth to everything from San Miguel Pale Pilsen to Budweiser. Ever enjoyed a crisp San Miguel Pilsner on a hot day? Thank the Wittelsbach clan!

The high quality of beer that was brewed after the law went in to effect convinced people fairly quickly of its value. Brewers were also proud of their ability to create such complex and clean beer using only three ingredients, and the Reinheitsgebot‘s place in Bavarian beer culture was cemented. In 1871, when the new German parliament enacted new taxes on beer nation wide, they made special exceptions for Bavaria, so as to allow them to preserve their competitiveness with other breweries using cheaper, lower quality fermentables. In 1906, certain North German states began adopting portions or all of the Purity Law, and–in 1918, when the Weimar Republic was founded following the end of World War I–Bavaria made its joining the new Republic conditional upon the entirety adopting the Reinheitsgebot. The Reinheitsgebot would remain binding upon German brewers until it was superseded in 1986 by Paneuropean regulations of the European Union, but many brewers still proudly advertise their voluntary adherence to these high standards of quality

Now, there are certainly some downsides to having such strict and inflexible regulations about what can go in to beer and what can’t. To illustrate, the adoption of the law by the entirety of Germany during its unification led to the extinction or near-extinction of many local brewing traditions and specialty beers, such as North German spiced and cherry beers. Indeed, to this day, German beers are dominated by the pilsener-style lagers that were popular in Bavaria, and only a few regional beer varieties outside of Bavaria such as the Kölner Kölsch or the Düsseldorf Altbier survived its national implementation.

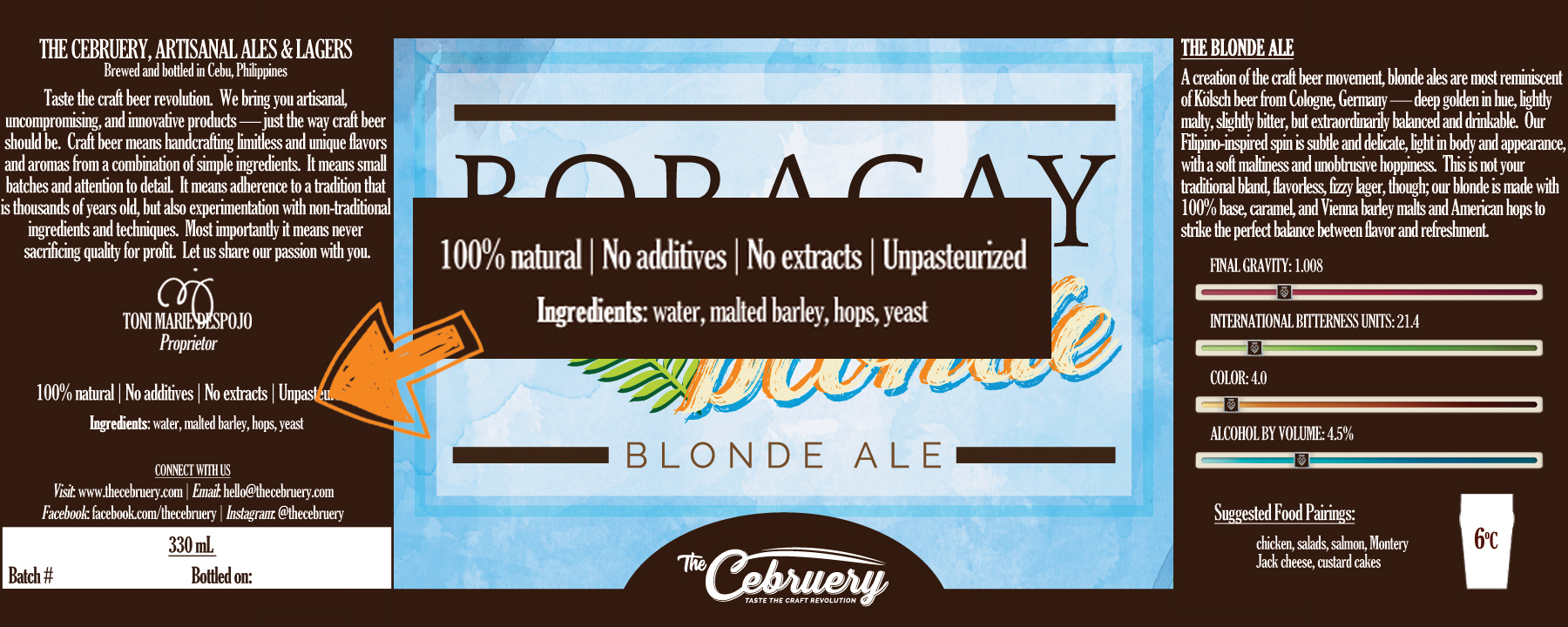

But the main principle behind the Purity Law–that ingredient quality matters, that purity matters, and that people deserve honesty and transparency from a brewer–are very much major values associated with the craft beer renaissance. Though the Cebruery doesn’t hold itself to inflexible rules about what can or cannot go in our beer, the vast majority of our beers are made with only 100% malted barley, hops, and water (we add some yeast, too – it’s not our fault 15th century Germans didn’t have any microbiologists on staff, and the beer wouldn’t taste very good without it, we promise). And when we do venture outside these limitations and add other fermentables like wheat or rye malt, dark brown sugar, pumpkin, or fruit, we do it to add flavor and complexity, not to make our beer less expensive to produce so we can make more profit.

And like those brewers in Munich hundreds of years ago through to the present day, we’re proud of what we make. We’re proud that we have enough mastery over our equipment and enough familiarization with the sciences and art of brewing that we can–using such a simple set of ingredients–make dozens of different flavorful beer styles, dark to light, hoppy to malty, low alcohol to high alcohol. We don’t need additives or preservatives or extracts or chemical flavorings, and you deserve a product you can be as proud of imbibing as we are of producing. So raise a glass to the Reinheitsgebot, the original consumer protection law, and rest assured that every glass of Cebruery beer rests on those same foundations that has made “German beer” synonymous with “quality” for hundreds of years!